A Raku Tea Bowl by Tamamizu Souske

Artist:Tamamizu SouskeEra:Edo/ MeijiPrice:$5,000Inquire:info@shirakuragallery.com

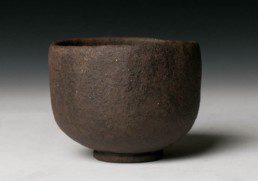

In the world of Japanese ceramics, Tamamizu-ware has an almost mythical standing. A branch of the main Raku line, at one time the two kilns held equal prominence, both being endorsed by the major tea schools of Kyoto and both being favored by the Imperial household. The first in the line was an illegitimate son of Kichizaemon Ichinyu (Yahē) who studied under his father and then left to open his own kiln in the village of Tamamizu (known today as Ide-cho). Though he is the first potter of the Tamamizu branch, he is usually referred to as Tamamizu VI (denoting his descendance from the Raku line). After establishing the kiln, Yahē took the artist’s name “Ichigen” and proceeded to fashion extremely high-quality tea bowls and other implements in the style of the earliest Raku potters. The tea bowl shown here is by one of the last potters of the Tamamizu line Souske XIII, born in 1837.

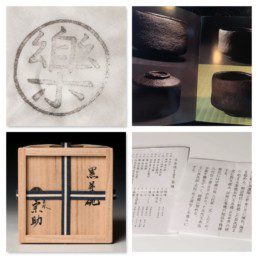

A book containing secret techniques used by the kiln has been handed down to each successive generation since the age of Dō’nyū (1599 – 1656). Unlike the main Raku line—that to a certain extent allows each generation of potter to follow their own aesthetic sense—Tamamizu potters have stayed true to the original forms set out by Chōjirō, Dō’nyū, and Kōetsu. The line of Tamamizu potters continued up to early Meiji with the death of Tamamizu 14. However, a recent attempt was made to revive the kiln by a descendent (later dubbed Tamamizu 15) who spent his life collecting Tamamizu-ware from earlier potters, researching the techniques used by studying old manuscripts, and training with main-line Raku potters. Despite these efforts, there remain many historical gaps in our collective knowledge of the kiln and of the individual potters themselves.

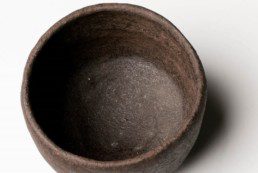

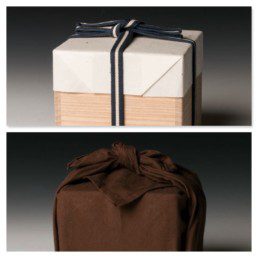

A beautifully crafted and remarkable example of Edo period Raku pottery, this tea bowl is 4.3 inches in diameter (11cm) and stands 3.4 inches tall (8.5 cm). It comes with a recently furnished certification box (likely by Tamamizu 15), a protective silk cloth with Raku seal, a wrapping cloth for the box in the same color as the tea bowl, and informational inserts in Japanese detailing the kiln and potters. As added documentation, a copy of a recent catalog on Tamamizu pottery is included showing matching stamp and providing additional information about the kiln and potters.